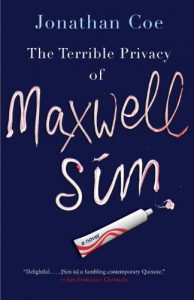

A Garrulous Sad Sack

A Garrulous Sad Sack

Review by Rea Keech

Maxwell Sim, the garrulous Sad Sack narrator of this 2010 satirical novel, is unable to connect with other people, even those in his own family. The story traces his pitiful, humiliating attempts to do so. One of my favorite scenes is when Max is trying to re-establish a closeness with his teenage daughter over dinner in a restaurant and they both end up texting other people on their cell phones. Another is the scene in which Max replies simultaneously to two different conversations by a husband and wife who aren’t listening to each other.

The tone is chatty, as if Max is talking to himself and sometimes directly to the reader. For example, Max introduces a new character, then says, “You’ll like her. I know you will.” In general, the novel is constructed by elaboration on an endless series of anecdotes in which Max (and the author) show their facility in rambling on and on about the least little thing. In addition to these drawn-out anecdotes, the novel makes considerable use of stories within the main story, told by other narrators. For example, there is a story of a sailing adventure that Max reads on a laptop and short stories by a childhood friend, his wife, and his father. These interpolated stories are told in a style not really different from Max’s own style. In describing this style, the words succinct, sparse, or economical definitely do NOT come to mind. The overall impression is a determination by the narrator/author to keep on talking. And yet, by the end of the novel, there is also an attempt to tie a lot of the apparently pointless anecdotes together, even if somewhat implausibly.

Satire? Maybe. There are some hints at the shallowness of contemporary society caused by the proliferation of nonproductive jobs—in banking and finance, for example—and the loss of manufacturing and creative activities. And one character complains about the way corporations have destroyed the individuality of communities and local businesses. Judging by the rest of the book, this would seem to be the author’s view, as well. But the narrator, whom we also sympathize with, says he likes being able to go to an identical chain restaurant in every rest area. Apparently, our world has been turned into a comfortable place for solipsistic Sad Sacks.